If you’ve spent any amount of time on TikTok you’re bound to have come across some video saying that if you bounce your legs or misplace your keys then you have ADHD. Similarly, being nervous for a job interview must mean you have social anxiety, or you’ve seen a meme about wanting to lay in bed all day instead of going to work or class and now you’re convinced you too have clinical depression. Social media has fundamentally changed the conversation around mental health, and it seems– at first glance at least– as though there is far more awareness in the general cultural zeitgeist about what mental illness is and what it entails.

However, this shift in cultural perceptions of mental illness may not actually be a wholly positive one. Particularly on TikTok, the way in which– and degree to which –certain mental illnesses are being destigmatized is arguably doing more harm than good. As I will outline below, TikTok has reduced mental illness to personality traits– ultimately deincentivizing recovery– led to rampant misinformation about symptoms, and further demonized psychotic and other disorders that cannot be reduced to “quirky” personality traits. What has changed is not total destigmatization of mental illness, but instead the pathologization of personality traits, which in turn ultimately harms those living with mental illness.

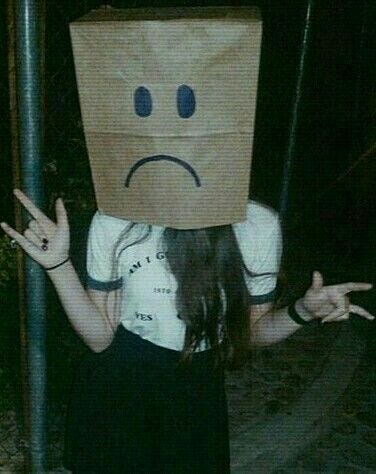

It is primarily through social media infographics, memes, and TikTok that depression, anxiety, and ADHD have been reduced to quirky personality traits; depression has become merely a word that describes an interest in blue hair dye or ramen noodles, and ADHD is now just silly flightiness or being distracted by sound. The quirkification of mental illness as I’ll call it has not only reduced depression, anxiety, and ADHD to personality traits, but also to common experiences such as introversion or being occasionally nervous. TikTok specifically has become known as a platform where people post about a common experience (distractibility, fidgeting, misplacing items) and pathologize them; according to large swaths of TikTok, experiencing one of those things automatically means that you have ADHD, being sad occasionally means you have depression, or simply being nervous must be anxiety.

Furthermore, the flattening of illness to personality is not just an abstraction; in social media’s deeming of depression as only sadness, anxiety as only nervousness, or ADHD as only forgetfulness, it has made it so that individuals with those illnesses see their experiences being reduced into common emotions. If depression is portrayed as only a negative mood then how do I possibly find room to share that I will go weeks without showering or days without brushing my teeth? I have thrown bowls away because food has been so crusted onto them from weeks of sitting in my sink. These elements– the dirty, sad, the ugly –are not mentioned on social media because, again, an illness that has been rendered quirky cannot simultaneously be seen as horrifying or debilitating.

It should be noted that humor is often a defense mechanism for those who experience serious mental illnesses (SMIs). However, the difference here is that it has become a societal joke and attitude, no longer confined to those who experience those illnesses; this expansion often leads to blatant misinformation about symptoms as memes about symptoms are reductionistic or, again, fail to account for the not so quirky elements of illness. The simplistic and one-dimensional viewing of certain mental illnesses has made it so that individuals–and especially adolescents– self diagnose based on only a few symptoms (especially ones that are often common experiences).

If depression is a quirky personality trait, then it has led people to take that label and hold on to it with force; due to social media, depression is a commodified social aesthetic that, like astrological signs or Meyers-Briggs types, comes as a ready made set of personality traits.

Previously, one platform renowned for doing this was Tumblr in the early- to middle-2010s, where liking music artists such as Halsey, the Arctic Monkeys, or the 1975 were inherent, sonic indicators of sadness or emotional unwellness. The grunge aesthetic was the epitome of teenage angst, and also teenage desperation or sadness, or a desire to be understood and feel like one was a part of something bigger. Teenage angst and depression–in all its social connotations, not necessarily clinical– were a way of connecting to others and understanding one’s self in broader culture.

Similar things have reemerged on TikTok and the algorithm has only intensified it. As the algorithm of TikTok keeps you in specific enclaves of the internet it can become easy to associate your illness with a sense of community, making it harder to separate illness from identity or a sense of belonging. For example, while Tumblr was one iteration of a sonic signifier, the likes of Phoebe Bridgers, (still) Lana del Rey, and Cigarettes after Sex have become the contemporary faces of teenage depression. Spotify even keeps an updated playlist called the “sad girl starter pack,” and it has amassed over 1 million likes. However, illness as pop-culture or identity fundamentally changes the experience of being ill.

The issue here is not just in identifying with others through illness and clinging to it, but our personality is oftentimes associated with identity and so conflating depression with personality leads to the adoption of depression as a whole identity. While building an identity around a diagnosis (largely through TikTok or sonic signifiers) may give one a false sense of security or community, it doesn't actually help one get better; if depression is a quirky and accepted personality trait on social media, then there is no incentive to discover an authentic personality outside of what is fed to you by the “sad girl starter pack” algorithm. (And, this is not to say that I necessarily believe that there is a "true self" that we can return to outside of illness, only that mental illness, no matter how quirky it is made to seem, should not be our whole social identity). In fact, in the identity illness model, which broadly examines the relationship between self-stigma and recovery, "self-clarity, hope, recovery and functioning," are negatively associated with viewing one's illness as their whole identity (as opposed to seeing it as something that is treatable, which has a better prognosis).1

Interestingly, there seems to be pushback on this societal destigmatization from people who do have clinical social or general anxiety, ADHD, or depression. It is hypothesized that “people diagnosed with SMIs [serious mental illnesses] may respond in three possible ways depending on the degree to which one believes that negative stereotypes are legitimate and [identify] with the ‘mentally ill’ group: indifference, righteous anger, and self- (or internalized) stigma. While indifference and righteous anger allow self-esteem to be unaffected by awareness of stigma, self-stigma is predicted to occur when people diagnosed with SMI identify as members of the group and believe that negative stereotypes directed at their group are true" [emphasis added].2 In an effort to legitimize the impacts of their own illness in a culture that has minimized mental illness to personality traits, many have adopted the model of self-stigmatization. Put differently, the apparent destigmatization of illness has instead led people to re-stigmatize their own illness in an effort to have their suffering be taken seriously.

The identification with illness, and the apparent (and false) ease of conceptualization of certain mental illnesses due to social media, has also impacted how society views illnesses that are not immediately understandable. Sadness, forgetfulness, and nervousness are far easier to conceptualize than illnesses that lead you to sleep in the same pair of pajamas every night for fear that something catastrophic will happen if you don't, or believe that the government is sending you messages through license plates. The "quirkiness" of the two makes bipolar, psychotic illnesses, or other serious mental illnesses seem extreme and out of the realm of relatability or empathy. In fact, in 2019 70% of the U.S. population reported believing that individuals with schizophrenia are violent.3 Stigma surrounding schizophrenia, psychosis, and other serious mental illnesses is pervasive in American society, especially where the value of an individual is often measured by their ability to participate in the workforce and contribute to the market; by portraying depression or anxiety as silly aspects of one's personality, the societal belief that those with psychotic illnesses are inherently violent is only intensified and the gap in understanding widened.

Again, this is not that anxiety and depression are not debilitating, only that social media's reduction of them to personality has made OCD, bipolar, and really any illness with psychotic features seem even less understandable in comparison. Social media has made only the quirky elements of depression or anxiety culturally acceptable and deserving of accommodation and, in the process, rendered those spewing conspiracy theories in the midst of a psychotic episode as not deserving of those things.

This divide in understanding seems most on display on TikTok. In early September of this year, Youtube and TikTok personality Gabbie Hanna, who has bipolar disorder, incidentally documented one of her manic episodes on her TikTok, leading many to mock her, call her insane, or worse, try to "cancel" her. On her TikTok she "began posting dozens of videos a day walking or dancing in mirrors around her California home while addressing her followers directly. Most of the rants centered around her belief in a higher power and destiny, others contained poetry dedicated to feminist ideas, and others were seemingly out-of-the-blue declarations — including claims that she was the second coming of Christ and how “Daddy” — her name for God — is now in charge of her Twitter and Instagram."4

Many of the rants contained transphobic or racist statements, again leading the internet to try to cancel her, mostly in the name of virtue-signaling. Part of the problem is that mania is often presented as a loosening of inhibitions like with alcohol, when in reality it often winds people up in jail, thousands of dollars in debt, or as was the case with Hanna, psychotic. Mania– in having the possibility to make someone believe in racist, transphobic, or otherwise hateful sentiments– makes it not quirky or easily understandable and therefore, in the eyes of social media, worthy of condemnation.

Mania (as defined by the APA): a period characterized by elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, often with several of the following symptoms: an increase in activity or psychomotor agitation; talkativeness or pressured speech; flight of ideas or racing thoughts; inflated self-esteem or grandiosity; a decreased need for sleep; extreme distractibility; and intense pursuit of activities that are likely to have unfortunate consequences (e.g., buying sprees, sexual indiscretions)

And social media, as seen particularly with the case of Gabbie Hanna, has led to the joyful, public surveillance of those experiencing acute symptoms of psychosis. In fact, Rolling Stone magazine covered Hanna's manic episode in an article titled "What’s Going On With Gabbie Hanna?" An individual's manic episode does not need to be covered by any prominent magazine– it's intrusive and dehumanizing. Hanna's sister, in the midst of Hanna's manic episode, publicly commented that "At the end of the day, you are all strangers on the internet and it is none of your business regardless of level of concern." Instead, individuals continued to mock Hanna, try to cancel her, or otherwise make her breakdown into a spectacle for all to witness and comment on. While mania is not something that can be hidden by the person experiencing it, that does not mean that they are deserving of their illness becoming a spectacle on social media.

Arguably, the same “cancellation” happened to Kanye West after his recent anti-semitic comments. The problem is that people fall into two camps in their beliefs surrounding manic behavior: believing that mental illness absolves you of all culpability, or believing that psychosis cannot make you do horrendous things that do not align with your morals or ego. Neither is true in its entirety; we must accept that mental illness can make you say or do hateful things, but this does not mean that those actions did not have impact or consequence. Just as one must pay the credit card debt they’ve wracked up in mania, one still has to own up to the hateful things they’ve said in that state. That being said, even as both Hanna and West have spewed hateful things and their comments had impact on minority communities, they are still deserving of empathy and help, and our inclination to turn away from them is only further proof that seeing depression or anxiety as quirky has further stigmatized bipolar disorder and psychosis.

Finally, I again cannot emphasize enough that depression and anxiety are truly debilitating disorders as well; the co-option of them as quirky or mere personality traits has harmed not only those living with those disorders, but also those living with other serious mental illnesses. Individuals, especially adolescents, living with depression or anxiety have begun clinging to those labels– leading to self-stigmatization– in an attempt to legitimize their own suffering in the face of a culture that has reduced it to mere sadness or nervousness. TikTok especially has taken this reduction and used it to encourage self-diagnosis as opposed to seeking help.

The quirkification of depression and anxiety has pushed those living with bipolar and psychosis (or really any illness that is not easily understandable) to the fringes of the conversation around mental health. Because these illnesses are not quirky, and cannot be painted as such, social media has further stigmatized them and only contributed to their demonization in broader culture. As seen with Hanna and West, the internet does not think those with psychosis are deserving of understanding and accommodation and has cast them off as horrible humans. Psychotic illnesses though are not straightforward; they are nuanced and chaotic and even if we can acknowledge the impact of statements made in psychosis, those living with psychotic disorders are still deserving of care and empathy.

Hasson-Ohayon I, Mashiach-Eizenberg M, Lysaker PH, Roe D. Self-clarity and different clusters of insight and self-stigma in mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2016 Jun 30; 240.

Philip T. Yanos, Joseph S. DeLuca, David Roe, Paul H. Lysaker, “The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness: A review of the evidence,” Psychiatry Research, Volume 288, 2020.

Melissa Healy, “Americans increasingly fear violence from people who are mentally ill. They shouldn’t,” Los Angeles Times, October 10, 2019; https://www.latimes.com/science/story/2019-10-10/americans-fear-violence-from-mentally-ill-people

CT Jones, “What’s Going On With Gabbie Hanna?,” Rolling Stone, September 2, 2022; https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/gabby-hannah-tiktok-podcast-dont-let-this-flop-1234584577/

there’s also this belief that the “normal” or “healthy” person is 100% well at any given time, which is used to simultaneously disprove the possibility/inevitability of change, separate oneself from the general public, and further support diagnoses of mental illnesses through those basic traits

rolling stone is a waste of paper